2011 Reunion

Attendees

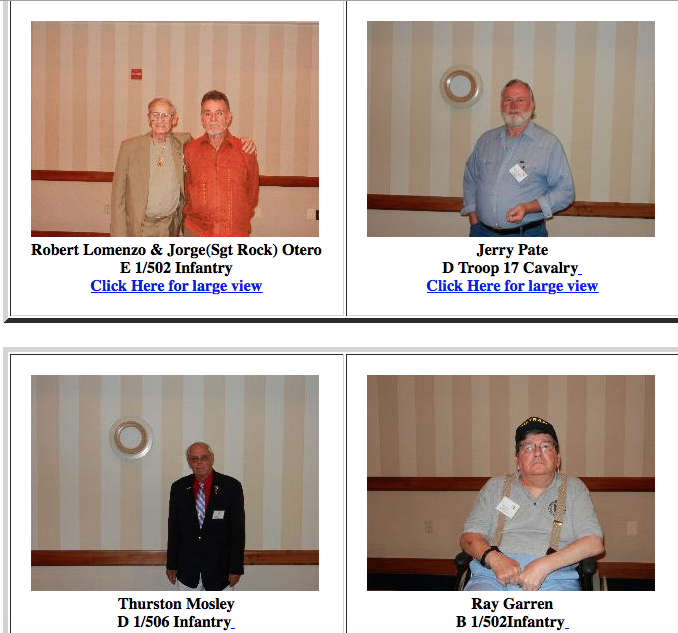

Thurston Mosley

Wally & Judy Morrow

Hector Colon Rios & Ana Hilda Santiago

Dave Nesbitt & Rosemary Bjork

Rodney & Helen Green

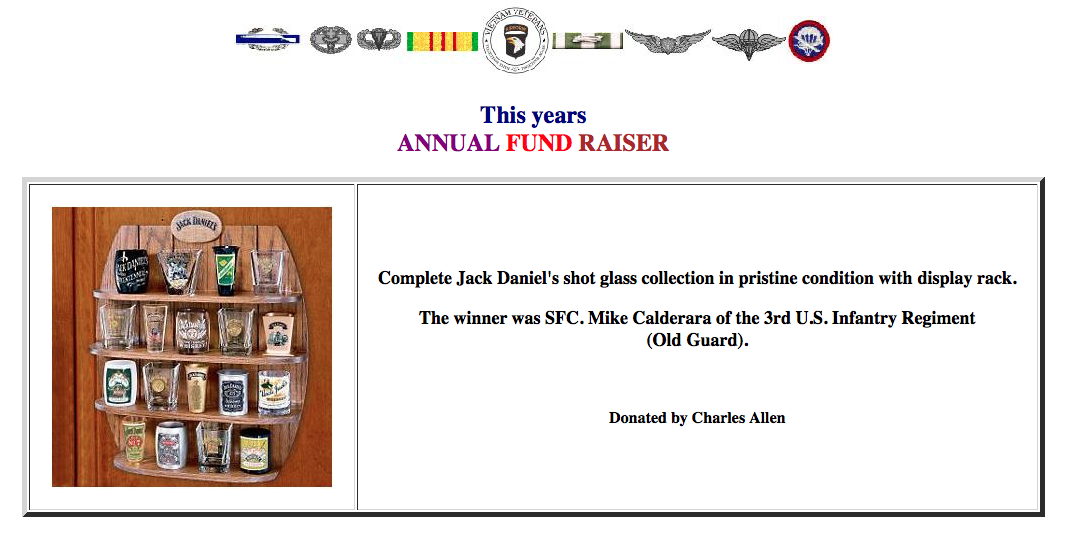

Charles & Ortaciana Allen

Che” Allen & Julie Guthrie

Albert & Emily Redd

Herbert & Susie King

James & Eugenia Holloway

Michael T. & Debby Garrigus

Frank & Anna Demory

LTG Ret. John H. Cushman

Freddy & Barbara Baker

Michael & Sharon Donovan

Gerald Laird

Robert Lormenzo

Karl Gerlach

Eddie & Linda Hollingsworth

James F. Hines

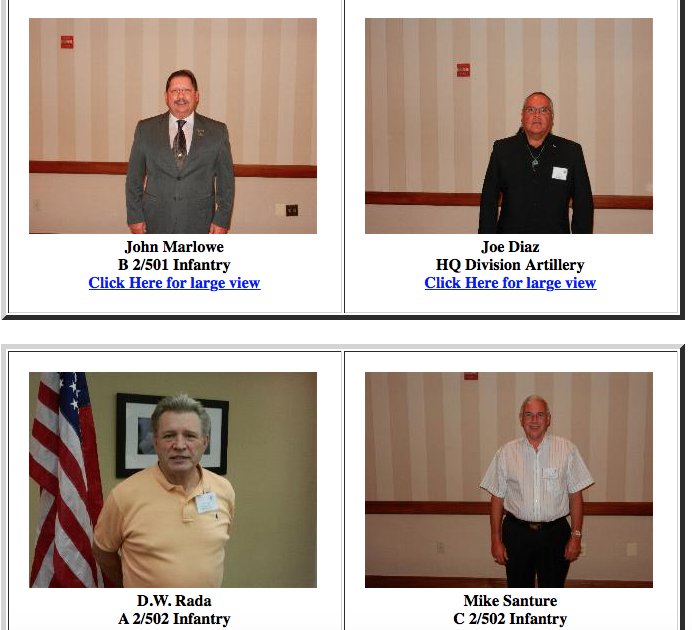

John & Mary Marlowe

Ed Barbour

Michael R. & Shelia Santure

Lee W. & Maurita Bostic

Sandy Bierhals

Jorge Otero

Ray L Garren

Janie Axelson

Jim Axelson

Mike & Bobbie Sellers

D. W. Rada

Rick Jestice

Malcolm Craig

Roger Craig

Bridget Salamie

Danny & Yolanda Cabral

Joe A. Diaz

Raymond "Butch" Garrett

Eddie Garrett

Patrick Hayden

Charles "Country" Cole

Charles E. Allen, Jr

Keith & Judie Lisenby

James Pearson

Wally & Judy Morrow

Hector Colon Rios & Ana Hilda Santiago

Dave Nesbitt & Rosemary Bjork

Rodney & Helen Green

Charles & Ortaciana Allen

Che” Allen & Julie Guthrie

Albert & Emily Redd

Herbert & Susie King

James & Eugenia Holloway

Michael T. & Debby Garrigus

Frank & Anna Demory

LTG Ret. John H. Cushman

Freddy & Barbara Baker

Michael & Sharon Donovan

Gerald Laird

Robert Lormenzo

Karl Gerlach

Eddie & Linda Hollingsworth

James F. Hines

John & Mary Marlowe

Ed Barbour

Michael R. & Shelia Santure

Lee W. & Maurita Bostic

Sandy Bierhals

Jorge Otero

Ray L Garren

Janie Axelson

Jim Axelson

Mike & Bobbie Sellers

D. W. Rada

Rick Jestice

Malcolm Craig

Roger Craig

Bridget Salamie

Danny & Yolanda Cabral

Joe A. Diaz

Raymond "Butch" Garrett

Eddie Garrett

Patrick Hayden

Charles "Country" Cole

Charles E. Allen, Jr

Keith & Judie Lisenby

James Pearson

Guest Speaker

LTG (then COL) John H. Cushman

The Second Brigade Task Force of the 101st Airborne Division

The Second Brigade Task Force of the 101st Airborne Division

General Cushman was born in Tientsin, China, son of Captain Horace O. Cushman, Fifteenth U.S. Infantry, of Danville, Illinois, and Kathleen O’Neill Cushman, of Charleston, South Carolina. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1940 and in 1944 graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He served with the 808th Engineer Aviation Battalion in the Philippines and Japan and in 1946 joined the 38th Special Engineer Battalion at Sandia Base, New Mexico.

General Cushman earned a Masters degree in Civil Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then attended the U.S. Army Engineer School. In 1951 he transferred to the Infantry branch, attended the Infantry School, and joined the 22d Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, in Germany where from 1951-54 he was a battalion and regimental executive officer and battalion commander.

He was a student at the Army Command and General Staff College, then served three years on its faculty. In 1958-60 General Cushman was in the Office, Army Chief of Staff; in 1961-62 in the Office of the General Counsel of the Department of Defense; and in 1962-63, a military assistant to the Secretary of the Army.

In 1963 General Cushman became Senior Advisor to the 21st Division of the Vietnamese Army in the Vietnam Delta. In 1964-65 he attended the National War College, reporting thereafter to the 101st Airborne Division, Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he was Director of Supply, Chief of Staff, and Commander 2d Brigade.

In December 1967, General Cushman led his brigade to Vietnam where it fought in the Tet 1968 battles around Hue. The 2d Brigade there earned the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm. He then commanded Fort Devens, Massachusetts, returning to Vietnam’s Delta in 1970 for duty as Deputy Senior Advisor, then Senior Advisor, to the Commanding General, IV Corps and Military Region 4.

In 1972-73, General Cushman commanded the 101st Airborne Division, its colors just returned from Vietnam, at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The draft having ended, he recruited the division under the Unit of Choice program and brought it to near full readiness. In 1973-76 he commanded the Army Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and was concurrently Commandant of the Army’s Command and General Staff College.

From 1976 to 1978, General Cushman commanded I Corps (ROK/US) Group, the 250,000-strong Korean-American field army formation defending the Western Sector of Korea’s DMZ and the ap-proaches to Seoul, He retired in 1978 and since then has been a writer and consultant. He is the author of many books and articles on strategy, multiservice and multinational operations, warfare simulation, and command and control of theater forces. In 1994 he was named “author of the year” for the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings.

General Cushman earned a Masters degree in Civil Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, then attended the U.S. Army Engineer School. In 1951 he transferred to the Infantry branch, attended the Infantry School, and joined the 22d Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, in Germany where from 1951-54 he was a battalion and regimental executive officer and battalion commander.

He was a student at the Army Command and General Staff College, then served three years on its faculty. In 1958-60 General Cushman was in the Office, Army Chief of Staff; in 1961-62 in the Office of the General Counsel of the Department of Defense; and in 1962-63, a military assistant to the Secretary of the Army.

In 1963 General Cushman became Senior Advisor to the 21st Division of the Vietnamese Army in the Vietnam Delta. In 1964-65 he attended the National War College, reporting thereafter to the 101st Airborne Division, Fort Campbell, Kentucky, where he was Director of Supply, Chief of Staff, and Commander 2d Brigade.

In December 1967, General Cushman led his brigade to Vietnam where it fought in the Tet 1968 battles around Hue. The 2d Brigade there earned the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm. He then commanded Fort Devens, Massachusetts, returning to Vietnam’s Delta in 1970 for duty as Deputy Senior Advisor, then Senior Advisor, to the Commanding General, IV Corps and Military Region 4.

In 1972-73, General Cushman commanded the 101st Airborne Division, its colors just returned from Vietnam, at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. The draft having ended, he recruited the division under the Unit of Choice program and brought it to near full readiness. In 1973-76 he commanded the Army Combined Arms Center, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and was concurrently Commandant of the Army’s Command and General Staff College.

From 1976 to 1978, General Cushman commanded I Corps (ROK/US) Group, the 250,000-strong Korean-American field army formation defending the Western Sector of Korea’s DMZ and the ap-proaches to Seoul, He retired in 1978 and since then has been a writer and consultant. He is the author of many books and articles on strategy, multiservice and multinational operations, warfare simulation, and command and control of theater forces. In 1994 he was named “author of the year” for the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings.

Join us as we take a meandering tour around Washington, D.C., to explore some of the capital city’s most famous memorials and monuments. At 555 feet, 5.5 inches, the Washington Monument is the tallest stone structure in the world. It is also the tallest structure of any kind in Washington, D.C., meaning that at some point during your visit—after the fifteenth or twentieth glimpse of it from a lot farther away than you’d have guessed you could see it—you’re bound to start wondering what the city looks like from the windows at its top. The answer is: it looks stunning. On a clear day, you can see twenty miles; but even on a muggy day, you’ll see far enough to appreciate Pierre L’Enfant’s boulevard-and-circle vision of city design, and to take in the way the Potomac sweeps to the south of Capitol Hill. To the north, you can look into the White House’s backyard. To the west, you’ll find the Reflecting Pool and the Lincoln Memorial; to the south, the Tidal Basin and the Jefferson Memorial; to the east, the whole length of the National Mall, all the buildings of the Smithsonian, and the U.S. Capitol. Around its base flutter fifty American flags, one for each state. Although it is now the most iconic landmark in Washington, D.C., the Washington Monument sat unfinished for an astonishingly long time. Congress first formed a Washington National Monument Society to raise funds for it in 1833, but bad fundraising, interference by the American Party (also called the Know-Nothings), and the Civil War conspired to leave it stalled as a hundred-foot stump for fifty years. Interest in completing the monument revived with the first Centennial in 1876. Congress appropriated the money necessary to finish it, and the capstone was finally put in place in 1884.

You may know the Thomas Jefferson Memorial from the many iconic photos of Washington, D.C., during cherry blossom season; it’s the monument that sits right on the Tidal Basin, surrounded by thousands of Yoshino cherry trees. Sure, the views from the memorial are stunning, but take a moment to ponder the man it commemorates: third U.S. president, drafter of the Declaration of Independence, and founder of the University of Virginia. Modeled on Rome’s Pantheon, designed by John Russell Pope, and dedicated in 1943, the memorial sparked controversy when it opened because it resulted in the removal of a swath of Washington’s beloved cherry trees. The nineteen-foot-tall, five-ton bronze statue of Jefferson in the center of the building looks toward the White House. Due to metal shortages during World War II, the statue was added four years after the memorial’s dedication. Five quotations from Jefferson’s writings line the inside of the memorial, including excerpts from the Declaration of Independence. Underneath the memorial, you’ll find a small museum and bookstore.FDR Memorial This meandering seven-and-ahalf- acre memorial—near the Jefferson Memorial, just off the Tidal Basin—pays tribute to both a president and an era. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s accomplishments during his four terms in office are honored through sculptures and words etched in four outdoor granite galleries representing time spans from 1933 to 1945. The thirtysecond president is shown in a bas-relief that depicts him riding in a car during his first inaugural, alongside his beloved dog, Fala.

Opened in 1997, the memorial spurred controversy when advocates for the disabled argued that Roosevelt should be depicted in a wheelchair, which he used after contracting polio in 1921. Because Roosevelt was careful never to be seen in his wheelchair in public, designers instead decided to include a statue of Roosevelt seated, covered in a cloak. The design also incorporates Braille in some of its relief sculptures, as an aid to visually impaired visitors. The park-like memorial is wellsuited to photo ops; tourists especially enjoy posing among the figures depicted in the sculpture Bread Line, which conveys the mood of the country during the Great Depression. You’ll also find a number of pools and waterfalls, and a statue of Eleanor Roosevelt. This is the only presidential memorial to include a tribute to a First Lady.

Korean War Veterans Memorial Dedicated in 1995 by President Bill Clinton and South Korean President Kim Young Sam, the Korean War Veterans Memorial is a moving tribute to the 1.8 million Americans who served during the 1950-1953 conflict, sometimes called the “forgotten war.” The memorial centers on nineteen lifelike steel statues of U.S. soldiers on patrol, dressed in full combat gear. The soldiers represent the four branches of the U.S. military and a cross-section of races and ethnicities. Sculpted by World War II veteran Frank Gaylord, they are placed among juniper bushes and granite strips meant to simulate the rough terrain of Korea. A pool of remembrance and Honor Roll commemorate the dead, missing in action, and prisoners of war among the U.S. and United Nations forces who participated in the conflict. Along the memorial’s north entrance lies a curb listing the twenty-two nations that provided troops or medical support as part of the U.N. response. On the south side of the memorial, there are three Rose of Sharon hibiscus plants, South Korea’s national flower. The memorial is centrally located, adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial and directly across the Reflecting Pool from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Lincoln Memorial No trip to Washington, D.C., is complete without a stop on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to appreciate the breathtaking view east across the Reflecting Pool, toward the Washington Monument, and beyond to the U.S. Capitol. This is the nation’s capital at its most majestic. Opened in 1922 and modeled after a Grecian Doric temple, the Lincoln Memorial is a fitting tribute to the U.S. president who steered the country through a bitter Civil War. Architect Henry Bacon designed the building, and Daniel Chester French sculpted the seated statue of Abraham Lincoln, nineteen feet tall and carved from twentyeight blocks of white Georgia marble. On the memorial walls, you’ll find inscribed the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s second inaugural address. The memorial’s thirty-six massive columns represent the twenty-five U.S. states at the time of Lincoln’s death as well as the eleven seceded Southern states; state names are inscribed above each column in the order in which they joined the Union. While you’re pondering the genius of Lincoln, take a moment to remember the many historic moments that took place at the memorial,

including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech; opera star Marian Anderson’s moving rendition of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee;” and, most recently, inaugural festivities for President Barack Obama.

Maya Lin designed the Vietnam Veterans Memorial for a course in funerary architecture at Yale University. She got a B-plus, but she submitted the idea to the national competition then under way to pick a design for a Vietnam memorial, and beat out more than 1,400 other entrants. When the plan was unveiled, it caused a minor scandal. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is like no other war memorial built before it: there is no triumphalism or celebration of bravery in it, just a long black granite wall engraved with the seemingly endless names of the Vietnam War’s dead. It was called a scar on the earth, a ditch, a slap in the face to veterans. Jim Webb, now a U.S. Senator from Virginia, called it a “nihilistic slab of stone.” There were accusations that a Communist had infiltrated the competition jury, and slurs against Lin’s ethnicity. It came very close to not being built at all. But it was built, and has become perhaps Washington’s best-loved monument. “I remember one of the veterans asking me before the wall was built what I thought people’s reactions would be to it,” Maya Lin has said. “I was too afraid to tell him what I was thinking, that I knew a returning veteran would cry.” She was right. Veterans and family members of those who served do cry in front of the wall, and it’s not hard to understand why. The polished surface of the stone gives the visitor a clear reflection of him or herself, superimposed on the 58,260 names of those who never came home (including 1,200 listed as missing, denoted by a cross rather than the usual diamond). It’s a simple, powerful juxtaposition—we the living, they the dead—that will move you even if you have no direct connection to the Vietnam War. Every day, people leave offerings at the foot of the wall; all of these, except for perishables like food and flowers, are collected by National Park Service rangers, tagged, and archived. A rotating selection is displayed at the National Museum of American History.

World War II Memorial The National World War II Memorial opened to the public in 2004, after three years of construction and seventeen years of planning.

The memorial occupies the former site of the Rainbow Pool on the National Mall, and consists of several elaborately encoded components. Surrounding a fountain retained from the Rainbow Pool are:

The memorial occupies the former site of the Rainbow Pool on the National Mall, and consists of several elaborately encoded components. Surrounding a fountain retained from the Rainbow Pool are:

a wall of 4,048 stars, each representing one hundred American soldiers who died in the war; two massive arches, one dedicated to the Pacific theater

and one the Atlantic; and fifty-six pillars engraved with the forty-eight states and various territories that contributed soldiers to the U.S. war effort. The site spans almost 7.5 acres, and more than four million people visit it each year. Although the memorial serves principally to honor those who gave their lives, their health, or their loved ones during World War II—in particular the sixteen million who served and the countless civilians who supported the troops from home—the site is not a somber one, and it functions also as a celebratory reminder of the American people’s capacity for great, communal sacrifice.